Shelby Marie Hadley is a Minnesota Army National Guard Veteran who was deployed twice as an Air Traffic Controller—Bosnia in 2003 and “Operation Iraqi Freedom” in 2008. She is involved in the St. Cloud area Veteran community and serves as Peer Mentor with Wounded Warrior Project and on the advisory board of Big Brothers Big Sisters of Central Minnesota. Shelby shared her military story by performing in The Telling Project’s play Telling: Minnesota 2015 at the Guthrie Theater. Shelby continues to give back to her community through volunteer work with Veterans service organizations and committees and projects advocating for Veterans, military service members, and their families.

Shelby Marie Hadley is a Minnesota Army National Guard Veteran who was deployed twice as an Air Traffic Controller—Bosnia in 2003 and “Operation Iraqi Freedom” in 2008. She is involved in the St. Cloud area Veteran community and serves as Peer Mentor with Wounded Warrior Project and on the advisory board of Big Brothers Big Sisters of Central Minnesota. Shelby shared her military story by performing in The Telling Project’s play Telling: Minnesota 2015 at the Guthrie Theater. Shelby continues to give back to her community through volunteer work with Veterans service organizations and committees and projects advocating for Veterans, military service members, and their families. Back in September, I mentioned on social media that I was participating in a 12-mile ruck march for military suicide awareness and prevention. In response to that, I had a friend reach out wanting to participate as well. However Carly is more than just any old friend; she is an Army battle buddy. I served with her in the Army and deployed to Bosnia with her in 2003-2004.

As Carly and I were walking the 12-mile route, she told me that some of her co-workers were surprised to hear that she would be doing this walk because she had never shared with them that she served in the Minnesota Army National Guard. Carly said, “I joined the military to get out of Aitkin. It really wasn’t a big deal”. This made me curious about how other female service members I served with felt about their service.

In 2003 Carly, Jamie, Linnea, and I deployed to Bosnia. We were young women, each with a different story but also the same story. These women are the only ones that know what it feels like to be at that place and time with me and also be a female.

Linnea shared with me, “I’m less comfortable with the whole Veteran thing. I don’t feel right with that title—deployment or not—not when it’s the same title given to my uncle who spent two years in Vietnam.”

When my two youngest children first met Jamie at a birthday party, I wanted to kick myself afterwards because of the way I had introduced her to them. I said, “Kids, this is Jamie, a former co-worker of mine.” I should have said, “Kids, this is my sister-in-arms, and I had the honor to serve and deploy with her while in the military”.

Why did I talk about my military service during that 12-mile ruck march I shared with Carly? For the longest time I had a hard time seeing myself as a Veteran. I imagined, like the community around us, a more typical (male) rendering of a Veteran. I remember not using the word Veteran specifically, and would instead say dismissively that I had served in the military. Even to this day, sometimes I still have to push myself to say, “I’m a Veteran” after two deployments and nine years in the Minnesota Army National Guard. The more I say it out loud, the prouder I feel of my service, and I know in my head and heart that this is a lasting part of my identity.

When we as women Veterans personally struggle with the perception of being a ‘Veteran’ and are unable to identify ourselves as military Veterans, how can we expect others to include us in their definition of Veterans? This is the first step in identifying the stigma we place on ourselves. All of our service looks different, but it is in no way less regardless of if we are men or women. We still served, and I implore women Veterans to be proud of that service and help redefine the perception of a Veteran.

It comes down to the fact that I have a little girl. I want my daughter to hear my story and know that a Veteran can and does look like her mother.

Marian Hassan is an empowering educator, consultant, and children’s picture book author. As an educator, Marian advises, mentors and trains lots of folks about areas in early childhood education, family literacy, program development, evaluation, and coaching. Lately, she has been speaking to dual language families and teachers about the importance of the home language to the development of the second language. As a writer, her love of literature began at an early age listening to relatives tell Somali tales, a natural backdrop of the rich oral culture of her native Somalia. She is the author of bilingual children's books Bright Star Blue Sky and Dhegdheer: A Scary Somali Folktale.

Marian Hassan is an empowering educator, consultant, and children’s picture book author. As an educator, Marian advises, mentors and trains lots of folks about areas in early childhood education, family literacy, program development, evaluation, and coaching. Lately, she has been speaking to dual language families and teachers about the importance of the home language to the development of the second language. As a writer, her love of literature began at an early age listening to relatives tell Somali tales, a natural backdrop of the rich oral culture of her native Somalia. She is the author of bilingual children's books Bright Star Blue Sky and Dhegdheer: A Scary Somali Folktale. Maria Asp is the Program Director and a teaching artist with the Children’s Theatre Company’s Neighborhood Bridges program, where she partners with classroom teachers to use storytelling and theatre to teach Critical Literacy to inner city public school students. As an actor, Maria has appeared in 22 productions with FRANK THEATRE as well as several independent films; she also plays and sings music.

Maria Asp is the Program Director and a teaching artist with the Children’s Theatre Company’s Neighborhood Bridges program, where she partners with classroom teachers to use storytelling and theatre to teach Critical Literacy to inner city public school students. As an actor, Maria has appeared in 22 productions with FRANK THEATRE as well as several independent films; she also plays and sings music.

Sun Mee Chomet is a St. Paul-based actor, activist, and playwright. Upcoming in 2016, Sun Mee will be in Mu Performing Arts production of You for Me for You in the Dowling Studio (Feb. 19-March 6) and the Guthrie Theater's production of Harvey (April 9-May 15). She will be Assistant Directing the Guthrie's production of Disgraced (July 16-August 28). She is currently working on a new piece through a TCG Fox Fellowship called The Sex Show, exploring intimacy and sexual stereotypes in the Asian American community.

Sun Mee Chomet is a St. Paul-based actor, activist, and playwright. Upcoming in 2016, Sun Mee will be in Mu Performing Arts production of You for Me for You in the Dowling Studio (Feb. 19-March 6) and the Guthrie Theater's production of Harvey (April 9-May 15). She will be Assistant Directing the Guthrie's production of Disgraced (July 16-August 28). She is currently working on a new piece through a TCG Fox Fellowship called The Sex Show, exploring intimacy and sexual stereotypes in the Asian American community. Shannon Gibney lives, writes, and teaches in Minneapolis. Her creative and critical work has been published in a variety of venues, including in the anthologies Parenting as Adoptees and The Black Imagination: Science Fiction, Futurism, and the Speculative. Her young adult novel See No Color was published by Carolrhoda/Lerner Books in November 2015, and she is currently at work on a novel about African Americans who colonized Liberia in the 19th century.

Shannon Gibney lives, writes, and teaches in Minneapolis. Her creative and critical work has been published in a variety of venues, including in the anthologies Parenting as Adoptees and The Black Imagination: Science Fiction, Futurism, and the Speculative. Her young adult novel See No Color was published by Carolrhoda/Lerner Books in November 2015, and she is currently at work on a novel about African Americans who colonized Liberia in the 19th century. Trista Matascastillo served 16 years in the Navy, Marine Corps, and Army National Guard. She currently serves as the Veterans’ Voices Program Officer with the Minnesota Humanities Center and as Chair of the Women Veterans Initiative, a non-profit advocating for equality and develops programming specific to the needs of women Veterans. Trista is a contributing author of “The Attorneys Guide to defending Veterans in Criminal Court” and has become a frequent blogger and public speaker. Trista was honored as the 2011 Woman Veteran of the Year. She and her husband Hector live in St. Paul with their five sons.

Trista Matascastillo served 16 years in the Navy, Marine Corps, and Army National Guard. She currently serves as the Veterans’ Voices Program Officer with the Minnesota Humanities Center and as Chair of the Women Veterans Initiative, a non-profit advocating for equality and develops programming specific to the needs of women Veterans. Trista is a contributing author of “The Attorneys Guide to defending Veterans in Criminal Court” and has become a frequent blogger and public speaker. Trista was honored as the 2011 Woman Veteran of the Year. She and her husband Hector live in St. Paul with their five sons.

John Baker is a partner in the Baker Williams Law Firm located in Maplewood, MN. John represents Veterans and service members in the criminal justice system and with a variety of legal issues that are related to their military service, including Veterans’ preference and military law. John chaired the initiative to start Veterans Courts in Minnesota. Minnesota Lawyer named John as an Attorney of the Year in 2010 for this work. In addition, John is active at the legislature in writing legislation to benefit Minnesota Veterans. John is chair emeritus of the MSBA Military & Veterans Affairs Section. John retired from the United States Marine Corps after 22 years of service. He currently travels the country teaching law enforcement on how to deal with Veterans in crisis.

John Baker is a partner in the Baker Williams Law Firm located in Maplewood, MN. John represents Veterans and service members in the criminal justice system and with a variety of legal issues that are related to their military service, including Veterans’ preference and military law. John chaired the initiative to start Veterans Courts in Minnesota. Minnesota Lawyer named John as an Attorney of the Year in 2010 for this work. In addition, John is active at the legislature in writing legislation to benefit Minnesota Veterans. John is chair emeritus of the MSBA Military & Veterans Affairs Section. John retired from the United States Marine Corps after 22 years of service. He currently travels the country teaching law enforcement on how to deal with Veterans in crisis. Odia Wood-Krueger is originally from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, and now calls Minnesota home. She is a District Program Facilitator for Minneapolis Public Schools in the Indian Education department. In her spare time she can be found cooking, exploring, or crafting. She and her husband Tim recently started their own bicycle company called Advocate Cycles.

Odia Wood-Krueger is originally from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, and now calls Minnesota home. She is a District Program Facilitator for Minneapolis Public Schools in the Indian Education department. In her spare time she can be found cooking, exploring, or crafting. She and her husband Tim recently started their own bicycle company called Advocate Cycles. Jack is a criminal defense attorney, former CIA officer, journalist, and storyteller. He is unique across the entire state of Minnesota and the U.S. as the only criminal defense attorney who is also a former Central Intelligence Agency Officer as well as a former prosecuting attorney. He has a national reputation and can be seen frequently on MSNBC, Al Jazeera, CNN, and other networks across the country. He is also a member of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and the Minnesota Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. He also hosts his own

Jack is a criminal defense attorney, former CIA officer, journalist, and storyteller. He is unique across the entire state of Minnesota and the U.S. as the only criminal defense attorney who is also a former Central Intelligence Agency Officer as well as a former prosecuting attorney. He has a national reputation and can be seen frequently on MSNBC, Al Jazeera, CNN, and other networks across the country. He is also a member of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and the Minnesota Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. He also hosts his own

Evan C. Tsai is a criminal defense attorney and a recipient of the 2014 Veterans’ Voices Award in the “On the Rise” category. He served as a United States Marine from 1994 to 1999.

Evan C. Tsai is a criminal defense attorney and a recipient of the 2014 Veterans’ Voices Award in the “On the Rise” category. He served as a United States Marine from 1994 to 1999.

Marya Morstad is the longtime host of the weekly arts interview program, “Art Matters” on KFAI-FM Community Radio. She produced the award-winning documentary, “Art and Spirit Matters: Arts and Religion in the Twin Cities” as well as the program “Art is Patriotic: Artists Respond to the Republican National Convention,” and has produced 80 audio portraits of Minnesota artists for

Marya Morstad is the longtime host of the weekly arts interview program, “Art Matters” on KFAI-FM Community Radio. She produced the award-winning documentary, “Art and Spirit Matters: Arts and Religion in the Twin Cities” as well as the program “Art is Patriotic: Artists Respond to the Republican National Convention,” and has produced 80 audio portraits of Minnesota artists for

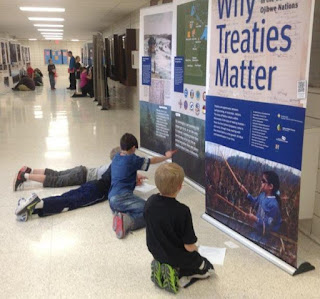

Marty Case works with Allies: Media/Art, researching the networks of people and businesses that represented the U.S. in treaties with American Indian groups. His work challenges the “master narrative” that shapes many assumptions about U.S. history and identity. He has also worked as Director of Development and Planning for a state-wide arts organization, and as writing and planning consultant to 45 widely diverse organizations in the fields of art, culture, education, social service, religion, and politics.

Marty Case works with Allies: Media/Art, researching the networks of people and businesses that represented the U.S. in treaties with American Indian groups. His work challenges the “master narrative” that shapes many assumptions about U.S. history and identity. He has also worked as Director of Development and Planning for a state-wide arts organization, and as writing and planning consultant to 45 widely diverse organizations in the fields of art, culture, education, social service, religion, and politics. David O’Fallon, Ph.D., is the President of the Minnesota Humanities Center. His vision for the Humanities Center is to transform education and find common ground to renew and strengthen our democracy through key work with partners. Prior to taking over as President of the Humanities Center, Dr. O’Fallon served as President of the MacPhail Center for Music, Executive Director of the Perpich Center for Arts Education, and Director of Arts in Education for the National Endowment for the Arts.

David O’Fallon, Ph.D., is the President of the Minnesota Humanities Center. His vision for the Humanities Center is to transform education and find common ground to renew and strengthen our democracy through key work with partners. Prior to taking over as President of the Humanities Center, Dr. O’Fallon served as President of the MacPhail Center for Music, Executive Director of the Perpich Center for Arts Education, and Director of Arts in Education for the National Endowment for the Arts. Meryll Levine Page served on the board of Minnesota Humanities Center from 2004-2012. Following her tenure on the board, she served as a consultant, drawing on her thirty-nine years of teaching experience. Meryll also blogs at:

Meryll Levine Page served on the board of Minnesota Humanities Center from 2004-2012. Following her tenure on the board, she served as a consultant, drawing on her thirty-nine years of teaching experience. Meryll also blogs at:

Sia Her is the executive director of the Council on Asian Pacific Minnesotans, a state agency that advises the Governor and the Legislature on issues of importance to the Asian Pacific community in Minnesota. She holds a master’s degree in public policy from the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs and a bachelor’s degree in political science from Macalester College.

Sia Her is the executive director of the Council on Asian Pacific Minnesotans, a state agency that advises the Governor and the Legislature on issues of importance to the Asian Pacific community in Minnesota. She holds a master’s degree in public policy from the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs and a bachelor’s degree in political science from Macalester College. Patrick Henry, who lives in Waite Park, Minnesota, was professor of religion at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania (1967-84) and executive director of the Collegeville [MN] Institute for Ecumenical and Cultural Research (1984-2004). Since 2007, he has been a monthly columnist for the St. Cloud Times. He joined the Minnesota Humanities Center Board in 2013 and is especially interested in fostering its work in Central Minnesota.

Patrick Henry, who lives in Waite Park, Minnesota, was professor of religion at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania (1967-84) and executive director of the Collegeville [MN] Institute for Ecumenical and Cultural Research (1984-2004). Since 2007, he has been a monthly columnist for the St. Cloud Times. He joined the Minnesota Humanities Center Board in 2013 and is especially interested in fostering its work in Central Minnesota.